Long, long ago, over the course of three centuries the little village of Palekh emerged as one of the leading centers of iconic painting in Russia. Its face and long traditions, however, changed dramatically after The Great Revolution of 1917. Because of the strong bond between the House of Romanovs and the Orthodox Church of Russia, the painting of icons was prohibited. Just as the Bolsheviks persecuted the Tsar and his court, they were also determined to rid Russia of anything related to the imperial family. The Church was among the first targeted.

Nearly overnight painters of icons were out of work. While many artists fled Russia for Paris and other western countries to continue painting icons, others remained in the small Russian village of Palekh where they eventually founded the Old Painting Artel in 1924. Determined to preserve the skills that a long line of fathers had passed down to their sons, and over many meetings sipping chai, they chose to use their talent to paint miniatures on black lacquer paper-mache boxes. And since these artists were encouraged to paint safe themes, many painters turned to Russian folklore and fairytales.

The telling of tales was an old tradition in Russia, keeping Tsars and Tsarinas entertained for endless hours. Storytellers were formally a coveted position where the oral tradition was passed down again from father to son. “This oral style of the folktale was important to the development of some of Russia’s greatest prose writers, such as Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Dostoevsky, among others.

Tolstoy remembered bedtime stories told to him by an old serf whom his grandfather had bought simply because he knew so many tales and told them so well.” (The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales, p 8.)

In the heart and mind of every Russian live the images of the Firebird, the Snow Maiden, Ruslan and Ludmilla, to name a few. Up until the artists of Palekh redirected their talents, these characters and tales remained primarily in Russia. But because so many artists brought these characters alive in their miniatures, interest in these fairy tales began to reach audiences well beyond Russia’s borders.

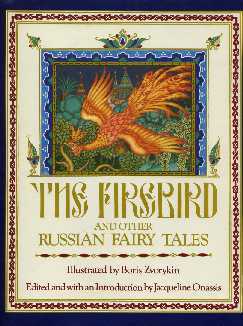

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis was so fond of Boris Zvorkin’s work in Palekh miniatures, she brought them to the United States.

Using experience of Lukutino miniature painting and art traditions of the Old Russian masters, Golikov started to create miniatures from fairy tales. His charming and original works fascinated his former colleagues of icon painting. Many joined his efforts.

Even their first works found a broad response among experts in Russia and abroad. The first exhibitions of Palekh in Paris and Venice made a sensation. Golikov’s miniatures, in spite of their size, expressed a spirit of time rather well. (Lacquer Miniatures Palekh, p 3.)

Folklore energy soon fed the soul of miniaturist-painters and helped to shape Russian culture as seen from within and perceived from the outside. “The most popular motif in a Palekh miniature has always been and remains the image of Zhar-Ptitsa or the Firebird, known as a symbol of beauty, eternal youth and happiness.” (Lacquer Miniatures Palekh, p 15.)

But this was not the only effort to fuel the birth of Russian fairy tales. Among those living in exile post revolution, Boris Zvorkin did his part, too. By crafting a book of fairy tales, he presented a gift of gratitude to his employer for a new life, celebrating all he valued and missed in the old. Like the counterparts he left in Russia, he, too, was drawn to the Firebird and named his book rightfully after the great bird of life.

Years after the Russia he knew had disappeared, Boris Zvorkin tried to recapture the richness of that distant culture he held in his heart. Against a backdrop of gray Paris skies, he painstakingly wrote out in French the Russian phrases long familiar to him, and brushed his brilliant colors into pictures of onion domes and flowing rivers, gray wolves and exotic princes. (The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales, p 6.)

As Russia embarks on a new journey post the fall of the Soviet Union, offering glasnost and perestroika to those who wish to express themselves without restrictions, many artists have returned to painting icons. Many more are looking for new forms of expression, sometimes denying centuries-old experience instilled by the Palekh masters to reflect the tastes of customers today. With the doors wide open and competing market tastes, I have no doubt that fairy tales will continue to remain a prominent theme among Palekh artists.